Barn Swallow

General Description

Known in Eurasia simply as 'the swallow,' the Barn Swallow is a distinctive bird with bold plumage and a long, slender, deeply forked tail. Barn Swallows are deep blue above, with an orange-buff breast and belly. They have russet throats and forehead patches. The rest of the head is deep blue, extending in a line through the eye, giving the birds a masked appearance. Females are slightly duller and shorter-tailed than males. Juveniles look similar to adults, but have much shorter tails.

Habitat

Barn Swallows need open areas to forage and suitable sites for nesting, now almost always buildings, bridges, or other man-made structures. They generally avoid unbroken forest and very dry areas. Their original habitat was most likely mountainous areas and seacoasts with caves, hollow trees, and rock crevices for nesting. Now that they have adapted to living with humans, they are found in agricultural areas, suburbs, and along highways--anywhere there are open areas and nesting structures, especially if water is close by.

Behavior

Barn Swallows can often be seen foraging for insects low over fields or water. In bad weather, they sometimes forage on the ground. They gather mud for their nests from mud puddles, although they do not raise their wings when they do this as Cliff Swallows do.

Diet

Barn Swallows eat mostly flying insects, especially flies, although they occasionally eat berries, seeds, and dead insects from the ground.

Nesting

While several Barn Swallows may nest near each other, they do not form dense colonies. They are usually monogamous during the breeding season, but extra-pair copulations are common, and new pairs form each spring. Polygyny sometimes occurs, and helpers not only help build and guard the nest but also incubate the eggs and brood the young, although they generally do not feed the young. A few birds still nest in caves, but 99% of the breeding Barn Swallows in Washington now build their nests on eaves, bridges, docks, or other man-made structures with a ledge that can support the nest, a vertical wall to which it can be attached, and a roof. Both members of the pair build the nest--a mass of mud, straw, feathers, and sticks. Barn Swallow nests are relatively untidy. Both members of the pair incubate the four to five eggs for 12 to 17 days, and both feed the young. The young leave the nest 20 to 21 days after hatching.

Migration Status

Long-distance migrants, Barn Swallows congregate along canals or field edges before they migrate in flocks, mostly along river valleys, to Central and South America.

Conservation Status

The killing of Barn Swallows for their feathers was one of the issues that led to the founding of the Audubon Society and the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. These outlawed the killing of birds without the appropriate license and made it illegal to possess even a single feather of a protected bird. The Barn Swallow's close association with humans in Europe goes back over 2,000 years. In North America, the shift from natural to human-made nest sites was nearly complete by the middle of the 20th Century. The Barn Swallow's range has expanded considerably in North America with European settlement, and Barn Swallows are widespread and abundant across their current range. Although they are still common in Washington, Breeding Bird Census data indicate that Barn Swallows have decreased significantly here since 1980.

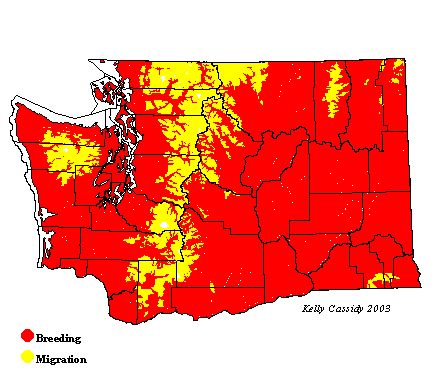

When and Where to Find in Washington

Barn Swallows begin to arrive in mid- to late April and continue to arrive into May; most leave by mid-September. They are common at lower to moderate elevations throughout the state in residential and agricultural areas, but in migration they may be seen in the mountains. They have been seen in Washington in the winter, but very infrequently.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | C | C | C | C | C | F | U | ||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | U | C | C | C | C | F | U | R | |

| North Cascades | U | C | C | C | C | F | ||||||

| West Cascades | F | C | C | C | C | U | R | |||||

| East Cascades | U | C | C | C | C | F | U | R | ||||

| Okanogan | C | C | C | C | C | C | U | |||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | C | C | C | C | C | U | |||||

| Blue Mountains | R | U | U | U | U | U | ||||||

| Columbia Plateau | C | C | C | C | C | C | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map